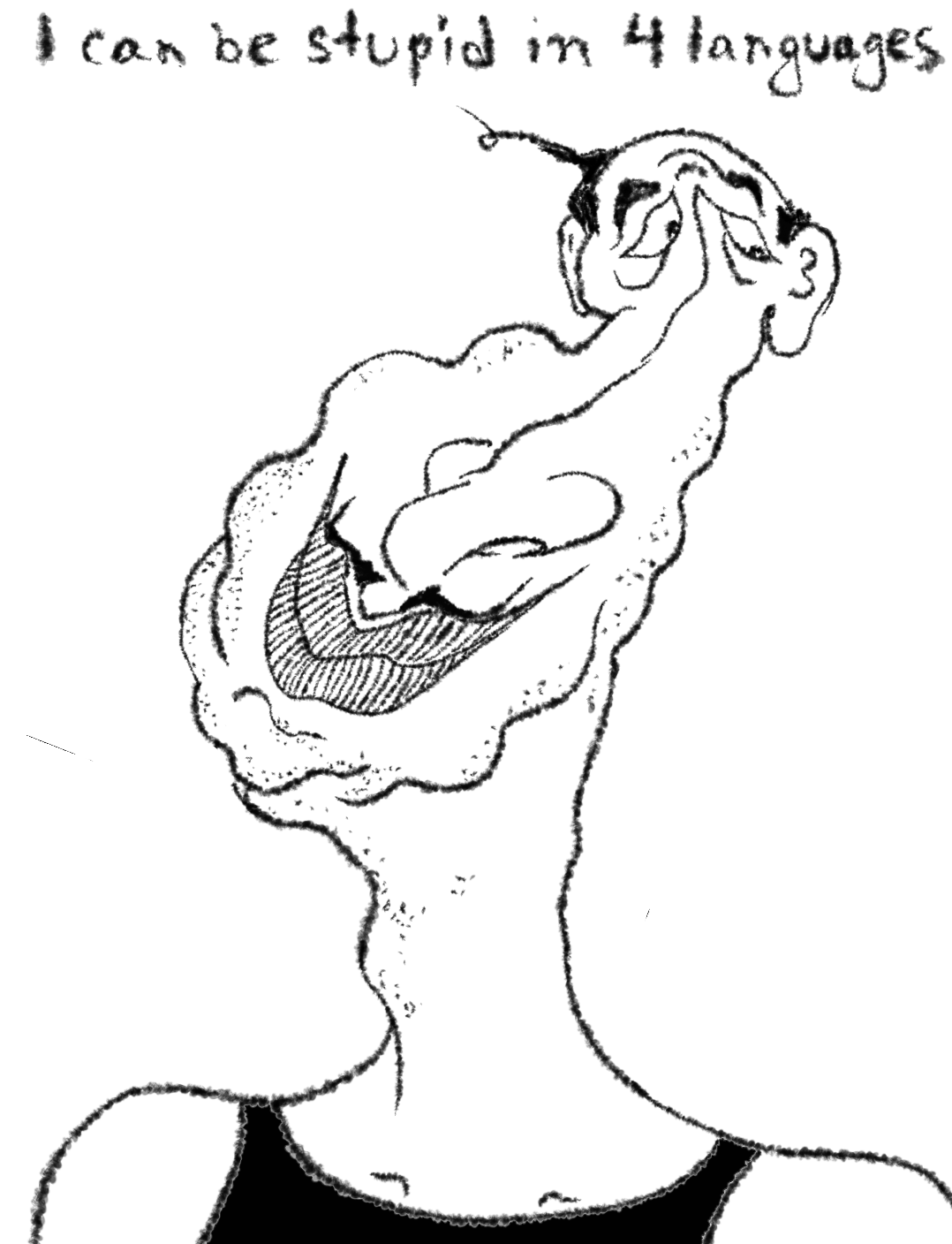

Stupid Multilingually

8/19/2025

The Indian problem with reality, as I have felt with NRI Indians in the US and elsewhere and especially, and largely in majority, in India, is with communication—particularly the ability to discern the gaps where the missing parts are, to imagine what the whole picture of the topic in question might look like, and to move past the general apathy, neglect, laziness, and mixed diffidence that together constitute and block the next steps needed to figure things out, to hunt for something etymologically or indeed to look for roots of affirmations, judging the veracity of the witness, the times, and the quality of recording possible before being convinced—not just for establishing the enduring attraction of bullshit over time but as part of the discipline of everyday life.

This can be easily exhibited by the lack of—or even when access or ownership isn’t an issue, the lack of—any felt need to look up words in a dictionary. If the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is to be believed, and we truncate our world to a few words, the resolution of thought shrinks, and I imagine a reciprocal of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis then takes form: the fewer words you know, the fewer distinctions you can even notice, and the fewer distinctions you can notice the fewer words you bother to keep.

The consequence is recursive and corrosive: nuance collapses into cliché, categories bleed into each other, and the mind learns to live on broad brushstrokes and slogans rather than fine contours and evidence. This is why legerdemain dressed in Sanskrit flourishes, pseudo-science, or slick corporate doublespeak finds such an easy market—language-impoverished minds cannot demand the specification, the mechanism, the numbers; they cannot hold two competing hypotheses in tension long enough to test them; they mistake rhetorical gloss for substance.

This is further compounded by a loose attention span that lets in a great deal of noise, so the original focal point dissolves into a larger, anomalous blob of combinatorially explosive, diffused paths, none of which are helpful to resolving the problem at hand. So, for example, the discussion turns to the price, the discount, the vendor’s ABCD details, but not the actual need for a product, nor the science behind it, nor the understanding of its specifications and how they match that need—or whether buying cheaper substitutes or fringe, unknown, low-merit baubles will turn out to be disastrous.

I was in Hyderabad where this was revealed to me: poor Muslims and poor Hindus are segregated by rich Muslims and by rich Hindus for the maintenance of patronage and privilege, for the preservation of property and polite optics, for the sanctification of inequality under the garb of charity, and chiefly to prevent any cross-communal class solidarity that might threaten the rentier arrangements that sustain them. I know, because although I am an atheist, in India, I am, and was identified as a high-caste Hindu Bengali, and my status as an Indian entrepreneurial NRI who had once employed over fifty people in Cybercity fitted that picture perfectly. But when I was robbed and massacred, when my family left me for safer grounds, I found myself living in the very neighborhoods from which the hired Muslim goons had come, where a Starbucks could still pretend to be American but everything else bore the scars of neglect—the central quarters where hardscrabble Muslims scrape by, abandoned to the great non-event of Indian secularism, that permanent collusion between a bearded Allah who never descends and a clean-shaven Vishnu who never stirs, which is to say: no roads, no drainage, no civic spine. And so I can tell you my story from inside that shared Hindu–Muslim, rich–poor dichotomy, not as a distant observer but as someone broken open by it, forced to live straddling both edges of the fracture at once. I discovered too while I lived in abject poverty, that it is not the familiar faces, nor the affluent or the influential from one’s past, who carry the greatest hearts. It was the poorest—Muslims, Christians, Hindus alike—who, when ranked by generosity and openness, stood tallest. They were the ones who offered kindness without calculation, who treated me not as a ruined man but as a fellow human in need. The rich, the kin, the so-called friends—once their self-interest had dried up—packed their bags with practiced ease, resolved never to recognize me again unless I could reappear as a source of income, a fountain of advantage they might once more sip from.

This synthetic Hindu-Muslim segregation I saw in Hyderabad is manufactured through durable and divisive fictions about each faction in popolar circulation since independence, land-use and tenancy decisions, through selective philanthropy and controlled endowments, through the placement of schools and clinics so that services are predictably parceled to one neighborhood or the other, through trusts and religious boards that gatekeep who gets relief and who remains indebted, through the cultivation of separate patron-saints and public rituals that naturalize separate loyalties; it is consolidated by political brokers who calculate votes in narrow communal units and by elites who pay for spectacle—temple façades, mosque madrasa renovations, festival largesse—that publicly confers moral supremacy while privately extracting labor and tribute.

The effect is surgical: it preserves elite wealth, converts moral language into a tool for social capture, and atomizes the poor into competing identity pockets so that basic questions of redistribution, of education, of scientific literacy, of civic infrastructure are never jointly demanded; in short the rich manufacture our blindness so the poor remain available as clientele rather than citizens, and that is precisely why the segregation is not accidental but deliberate, a convenient architecture of inequality dressed up as piety.

Multiply that impoverishment across languages and platforms and you have the multilingual dimming—con artists need only translate the same moral emptiness into five tongues and the effect is amplified, not checked. The diffusion in attention is multilingual, which makes it even more profitable. If people can be conned simultaneously in four or five languages, then why not? That is where we are. As Indians, we can be stupid multilingually. And multi-religiously too: the mixture of language and religious adjacency is deployed to segregate and blindfold people into brittle groupthink, a stratagem that damages both the internal life of each group—where inquiry is displaced by ritual, nuance by catechism—and the space between groups, where common facts are mistrusted, common needs are contested, and every possible alliance for public reason is atomized into reciprocal suspicion and grievance, leaving the polity poorer, more brittle, and less capable of collective problem-solving.

As I was caught up in this underside in Hyderabad as an entrepreneur; local goons, hired across communal lines by a businessman who wanted my company extinguished, came for ClinZen and for everything that tethered me to a life I had fought to build. They razed the company’s records, they looted my home, they stole my passport—everything I ever owned under the ClinZen name is gone now, scattered in somebody’s house I will never find. My childhood photographs, the rough drafts and notebooks of my work, the visible proof that I had once lived another life—all of it taken. My library of over fifteen thousand books, the material cargo I carried back from the United States, the margins full of my notes and the dog-eared pages that taught me how to think; I imagine those pages now as stove-fodder somewhere in central Hyderabad, or stacked in a goon’s courtyard as if the only thing they were ever fit for was fire.

The theft was not mere burglary but an erasure. The more I try to name what was stolen the more the loss feels like a removal not just of property but of history—of the record that I existed as someone who read, who argued, who built. That erasure was engineered: muscle deployed by patrons to protect privilege, violence purchased to tidy away inconvenience. Don’t get me wrong: these goon men, the penumbra of rich people that pay them, the umbra of the petty, imbecilic and subverted Indian democracy in which criminality is everywhere, where criminals are hired, tolerated, pensioned in petty municipal sinecures, given protection by police who prefer the stability of predictable violence to the mess of impartial law, granted contracts or bits of land that convert loitering into loyalty—these are the small armies that guarantee spectacle; their existence is insured by money, by impunity, by the tacit calculus that blames the other religious, minority or ethnically convenient community rather than the patron who profits. Both sides, the Hindu as well as the Muslim, preserve this segregated goon kingdom; the muscle is a commodity, the menace a service cultivated with surgical intent by brokers who know how to translate fear into control. They do not merely take what you own; they take the possibility that you will ever sit at the same table again and be heard. Few entrepreneurs will even ever get to the point where I was at, even I cannot recreate those privileged coincidences in times if I had money today. Of course it’s a different tragedy now, that I am beaten, battered and although I’m still alive my dreams are all dead.

But my point in bringing up my past is that the result of a corrupt India, of a India ruled by stupidity is a sad performative pathology: ideas that build a nation die premature deaths, entrepreneurship is raped and murdered, dogmatic provocations are engineered, rumors are fanned, processions are timed to create flashpoints, social media is milked for outrage and then drained when the mood suits the broker, and the necessary narrative is stitched into a mythic India–Pakistan scale enmity that, in reality, is a fiction reinforced daily because it is useful. That fiction serves two convenient functions at once: it distracts from economic dispossession and public failure, and it converts potential cross-communal solidarity—where a worker, Muslim or Hindu, might discover a shared interest with his counterpart—into suspicion and fury, ensuring the clientele polity remains fractured and therefore rentable.

This revealed underside is transactional, banal, and engineered: money flows to thugs, thugs supply fear, fear is monetized by politicians who trade votes for protection, and the whole arrangement is cosmetically sanitized as “sentiment” or “tradition” when convenient; none of it requires theology, only the willingness of elites to weaponize identity as a glue stronger than civic institutions. The fiction is useful because it is profitable, and the more convincing the antagonism appears, the less the poor ask for schools, hospitals, safe water, or scientific literacy—because their energy is diverted to defending identity theatres curated by the rich who need no defense at all.

Any trick long stale in the West is still a viable marketing ploy here, including the skipping of science and decent engineering altogether and opting for flat-out white lies. As long as they are linguistically dressed up whorishly, people lap them up.

To the leaders the citizens are a slimy, pre-diarrhea, brown, cringy coiled mass of illiterate idiots easily ruled. And so we have a subverted democratic dance by the dunces dictating dipshit dictums in Sanskrit or pig Latin only because they fucking can and therefore very well will. Modi nationally and Mamata here locally both do this diligently in at least three different languages, their exhortations played endlessly on their bootlicking paid channels in endless cycles by highly paid, well-dressed, spineless talking heads.

This is even more a happy state of affairs in an imposed Hindoo state, a reluctant but otherwise science-resistant culture, insular and rabid, a mob to whom the cryptic overuse of Sanskrit by men with fangs, in equivocal trite overpromises, isn’t at all suspect.

स्वल्पार्थयुक्तं बहुशब्दयुक्तम् ।

श्रुत्वा न जानन्ति जनाः पदार्थं

मन्दाः सदा मूढपरीतबुद्धिः ॥

svalpārthayuktaṁ bahuśabdayuktam

śrutvā na jānanti janāḥ padārthaṁ

mandāḥ sadā mūḍha-parīta-buddhiḥ

"This speech is exceedingly hard to understand—laden with many words but containing little meaning. On hearing it, people do not grasp the substance, for fools are always possessed by deluded minds."

(Hitopadeśa, Mitralābha 74)

अन्धा यत्र गता नराः ।

तत्राबुद्धिः प्रलीयेत

स्वबुद्धिं न प्रयोजयेत् ॥

andhā yatra gatā narāḥ

tatrābuddiḥ pralīyeta

svabuddhiṁ na prayojayet

"The blind indeed lead the blind, and wherever those blind men go, there the witless perish too, never using their own reason."

(Mahābhārata, Śānti Parva 109.10)

महाजनो येन गतः स पन्थाः ।

mahājano yena gataḥ sa panthāḥ

"The truth of dharma lies hidden in a cave; the path is simply the one on which the multitude has gone."

(Manusmṛti 7.52)

प्राणैरपि प्राणिनां संश्रयन्ते ।

किं तु प्रपञ्चस्थितये नृणां सदा

वाग्भिः प्रलापा बहवो भवन्ति ॥

prāṇair api prāṇināṁ saṁśrayante

kiṁ tu prapañca-sthitaye nṛṇāṁ sadā

vāgbhiḥ pralāpā bahavo bhavanti

"The words of the noble are never empty, for they cling to life itself. But for worldly men, endless chatter arises only to preserve appearances."

(Bhartṛhari, Nītiśataka, verse 5)