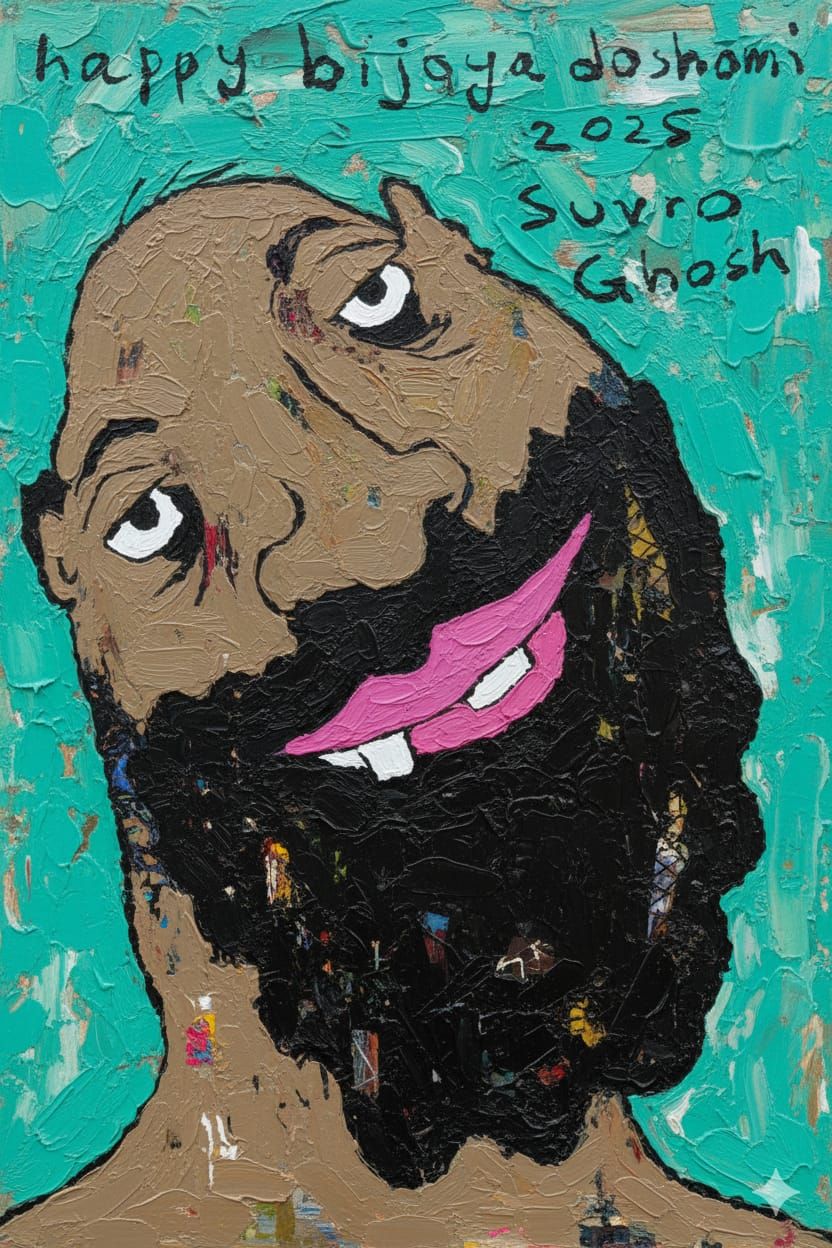

Durga goes home 2025

10/2/2025

Well at least Durga the poor disposable Chinese girl gets to go home, unlike the other billions of non-disposable Chinese plastic parts of her millions of fuckface devotees that will now get stuck in pipes and sewers, flung around hither and thither—because, fuck it, we are Indians. Because she of course has to go back to China, that’s the way the fiction is written to please and repeat in endless cycles. Or if you insist on the literal, physical geography, then to Kailash, the Tibet Autonomous Region of China.

She can, for a while, finally rest in peace. China is a far better maintained country, where drains don’t cough up dead gods, where the state at least pretends to value order, while we—armed with cymbals and bhog-laden hands—proceed to drown the goddess herself in the very water we claim to revere. We give her five days of adoration, tilaks and turmeric, then chuck her into the Ganga like she’s a plastic bag of takeaway biryani.

That is Bijoya Doshomi in the real world: a smoky, tearful farewell where the women rub vermilion into each other’s cheeks as if they’re coloring the sky itself, while municipal workers downstream are already waiting with bamboo poles to hook out a bloated papier-mâché lion or a plaster torso lodged in a weir. It is at once poetry and municipal murder.

The ritual is scripted as the daughter’s return to her mountain home, but the reality is she’s reduced to pollutants bobbing between empty soda bottles, a goddess choking the same river her devotees drink from. In Tibet, at least, her symbolic home, glaciers grind on in silence. Here, her “immersion” is indistinguishable from littering. The farewell, so drenched in sentiment, so moist with memory, is environmental vandalism dressed up in conch shells and brass.

That is the split-screen genius of India: the lamenting house that cries out “ashchhe bochor abar hobe” (next year it will happen again) while simultaneously ensuring the next year’s river is slightly more toxic, slightly more incapable of sustaining fish, slightly more a graveyard for God’s. It is satire written by the hands of millions and performed with the utmost sincerity, the only theatre where the goddess is wept for like a daughter, then treated like municipal waste, and somehow both truths coexist without embarrassment.

Now, if you trace the arc backward, the irony only thickens. Once upon a time, in agrarian Bengal, Durga was worshipped in homes, in small clay forms, a domestic goddess who came and went without fanfare. Then the British arrived, and with them came colonial excess. Wealthy zamindars threw massive pujas to impress the Company sahibs—lavish pandals, banquets, fireworks—part devotion, part social theatre. By the 19th century the puja had slipped out of the courtyard and onto the street. It wasn’t just about worship anymore; it was about spectacle.

Enter the nationalists. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, the same street pujas doubled as places for Bengalis to gather, to talk, to plot, to dream. Durga became more than a goddess—she was Bharat Mata’s stand-in, the motherland in divine drag. Singing to Durga meant singing to the idea of India. The British couldn’t exactly ban a religious festival, so politics smuggled itself inside the ritual like a spy under a veil.

And that’s how we arrive here, in 21st-century Kolkata, where Durga Puja is equal parts Broadway show, tourism brochure, and ecological crime. Pandal designers reinvent Paris, Rome, Mars, Hogwarts; sponsors stamp their logos under chandeliers of LEDs; lakhs of people surge like ocean currents through the city streets. For five days the air itself seems perfumed with fried food, incense, and exhaustion. Then, on Bijoya Doshomi, with tear-streaked faces and conch shells blowing, the idols are led to the riverbanks. Women smear each other with vermilion in a ritual that looks like an explosion of joy. And then—the goddess is heaved into the current with a splash.

If you watch closely, the split-screen is brutal. On one side the symbolism: a daughter going back to her mountain husband, a people promising she’ll return next year. On the other side the physics: paint flaking into the current, bamboo frames bobbing downstream, municipal cranes waiting to dredge the mess out by morning. It’s myth colliding with garbage disposal.

Meanwhile, her “real” home in Tibet is silent. Glaciers grind on, peaks rise in crystalline indifference, the air is too thin for theatre. There, the goddess can be imagined resting at peace. Here, she is a soggy idol floating among gutkha wrappers.

So Bijoya Doshomi is less a festival than a palimpsest of Bengal’s history. Agrarian myth, colonial display, nationalist politics, consumerist kitsch—all piled one on top of another, like clay over straw over bamboo. A single immersion scene contains three centuries of cultural history, condensed into one absurd and moving act. Durga is daughter, goddess, nation, Broadway diva, municipal waste.

That’s the peculiar genius of India: only here could an ecological disaster also be a love story, a political allegory, and a tearful family drama, all enacted simultaneously on the banks of a dying river. But I look forward to the sweets but I know the people around me are cheapskates so I’ll have to buy them myself whenever my payment arrives. Tea time, between now and the new year, will be my kingdom, my consolation prize, my sugar parliament. Not the tired Marie biscuits that dissolve into wallpaper paste the second they hit hot tea, not the stingy handful of Parle-Gs. I mean the real parade: cakes, biscuits, sweets, and yes, the occasional foreign invader, smuggled in by me if no one else will bother.

Biscuits are the opening act. Bourbons with their pseudo-chocolate cream, Good Day cashew with its buttery ridges, Danish butter cookies in their round tins that always end up holding something else less dear. Then the Indian staples: crumbly nankhatai (naan-kha-taai, from Persian roots, meaning literally “bread biscuit”), rich with ghee and cardamom.

Cakes form the mid-season crescendo. Fruit cake dense as geology, sponges frosted in neon pinks that no strawberry ever dreamed of, the quiet dignity of suji cake. And then—because tea deserves diplomacy—I’ll bring in the French. Imagine setting down a financier (fee-nahn-ssyay) beside your cup: a little almond tea-cake, originally baked by Parisian bankers who liked something neat enough to slip into pockets without staining their money. Or the feather-light madeleine (mad-lenn), shell-shaped, which Proust turned into a literary time machine.

If I can stretch my rupees far enough, I’ll try a tarte tatin (tart ta-tan), an upside-down caramelized apple tart born of a mistake by the Tatin sisters in their inn, now immortalized as elegance itself. Or the humbler palmiers (pahl-myé), also called “elephant ears,” puff pastry sugared and folded until it crisps into sweet, delicate scrolls. Even saying the names feels like licking sugar from your fingers.

And that’s not to overshadow our own mithai cavalcade—sandesh, rasgulla, gulab jamun, kaju katli—each sugar bomb as ceremonial as a coronation. But I like the idea that my tea table could be a little United Nations of sweets: Bengal lending the syrup, France the finesse, Denmark the butter tins, and Britannia the biscuits.

So between now and New Year, the plan is simple. Every evening, a cup of tea crowned with something different, something that reminds me that even if the people around me are cheapskates, I can still buy my own civilization in sugar, one bite at a time.