An ordinary morning

8/19/2025

An ordinary morning in Calcutta is anything but ordinary, for the city has never truly learned the art of waking gently. It does not yawn or stretch—it detonates. Before the sun has so much as tugged its head over the flat line of the horizon, the crows have already declared war. They descend like feathered prophets of doom, unleashing a cawing so apocalyptic it could convince one that the world has, in fact, already ended and this racket is the afterlife. There is no snooze button here, no mercy. The city wakes you as it wakes itself: abruptly, noisily, without apology. And to soften this jagged morning landing—as an antidote—there is this bread—not the packaged sliced kind, but the impossibly soft, still-warm cuboidal whole buns that arrive factory fresh at dawn in wicker baskets, or ferried in the cycle-borne vendors who seem to glide through the city’s lanes like silent priests of carbohydrates. These breads, called pauruti, are Calcutta’s own take on the colonial loaf, but they are fluffier, more yielding, the kind of bread that gives way at the faintest pressure of your thumb. Bought fresh, often with a smear of butter that melts instantly in the humidity, or dunked into a cup of sweet, overboiled tea, they are both breakfast and benediction—comfort food for a city that insists on starting the day in chaos but will, at least, offer you something tender to bite into while you endure it. This is why I live, for the taste of this bread, in my morning tea—my life is mostly made from these simple inexpensive things.

Kolkata, rechristened in 2001, when I was in the US, in a vainglorious bid to reclaim some post-colonial dignity, remains stubbornly Calcutta in spirit. The new name fits on signboards and government decrees, but the old one lingers on tongues and in memory like the comfort of a worn-out sweater. The buildings agree. Those hulking relics of British imperial ambition—once proud, now half-embarrassed and in ruins—stand along the avenues as dowager queens, plaster flaking in tired sheets, their weary grandeur mocking the modern hurry below. They were once cathedrals of power; today they accommodate call centers mostly to scam westerners—a morbid colonial revenge unknowingly playing out as commerce, leaking ceilings as leaky as the local scruples and morals of the place, and families packed like unsaid prayers into crumbling rooms.

The air of the morning is usually already dense, a stew of contradictions. Diesel exhaust from the lumbering yellow Ambassador taxis thickens it into a chewable fog, while somewhere nearby, oil spits and hisses as a vendor drops a round of dough into bubbling fat, the luchi inflating like a small miracle. Underneath it all, there lingers the moist, metallic breath of the Hooghly River—a sluggish, all-accepting artery that has, since Job Charnock’s day, borne faith, commerce, and filth with the same impartial dignity.

No morning here is complete without adda. To call it conversation is to call the monsoon a drizzle. Adda is Calcutta’s unofficial parliament, a sprawling forum that requires no invitation but insists on opinion. It unfolds around cups of tea—chaa—served in fragile clay bhaars, the tea itself thick, gingery, sweet as memory. Once drunk, the cup is hurled to the ground, shattered to dust in a symbolic homecoming. In these circles, time dissolves. The topics range from politics to cricket umpiring, from Tagore to the futility of life itself. It is not mere talk; it is collective self-examination, the city thinking aloud through its millions of mouths. Of course these are imagined. I have no one to talk to; I just have this blog—just myself. Most conversations are, for me, too empty and devoid of what I yearn for: some sort of connection to who I am, what I am doing here. And so I enjoy my reticence against the garrulous city. And even visiting a tea stall is rare; I hardly ever leave my room. I’m sort of incarcerated in my own habitual and attended loneliness—the kind I can at least manage with medications, with small excursions to the verandah to see if the world exists as they say it does.

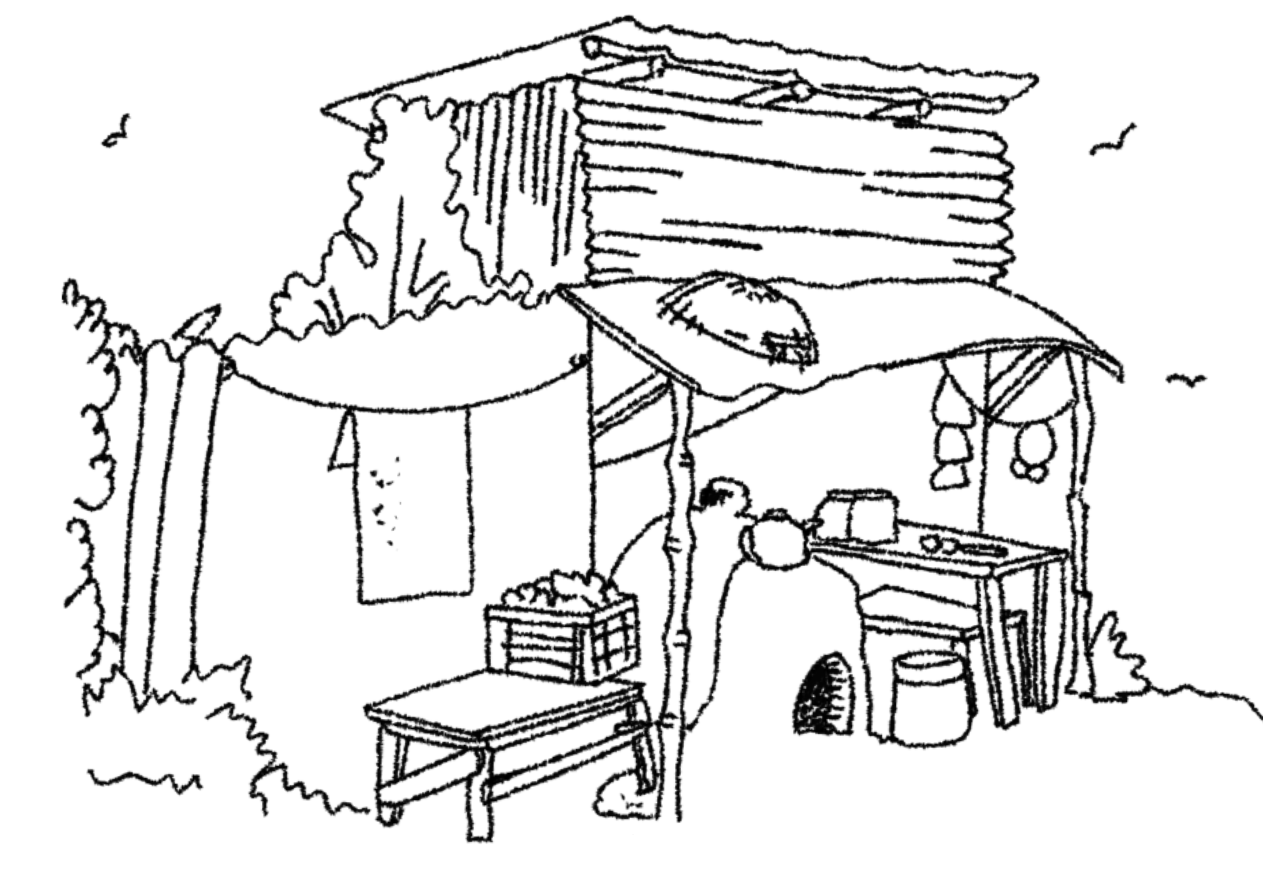

This tea shop I sketched is just around the corner, and you’ll find millions like it scattered throughout the country—places that to any American would seem far removed from the carefully engineered chains they’ve grown accustomed to. These are, in a sense, minions to a Starbucks or Seattle Coffee, ramshackles on stilts, yet they operate on a business model that at least helps a small family survive. The quality and variety of tea and biscuits aren’t especially diverse, but the germs are reliably killed when the water and milk are boiled—often safer than drinking water itself. Still, the same heavy metals, arsenic, and general filth are sipped with the sort of fastidious leeway we also extend to expired biscuits and cakes in tea stalls across the country.

Starbucks under Indian oversight is only as good as the rigor of health and statutory inspections. If those fail, then you are not only sitting in an America you may hope India never becomes, you are also paying far too much for the corruption and filth hiding behind the cheap substitute chai they never tell you about—while you suffocate in the stuffy air of an air conditioner whose filter hasn’t been changed in a long while. Starbucks became the star of India’s mainly coolie status, and unless business process outsourcing is reinvested into building something real, we will see the demise of these false artifacts of self-indulgence, surrogates of the new sort of slavery.

Around the early morning chatter of these tea stalls, the machinery of the day clatters, often unceremoniously, into incessant brisk and routine gear. The trams, those skeletal anachronisms, rattle their way past honking buses and motorbikes. Hand-pulled rickshaws—men yoked like beasts—creak and dart, archaic and shocking in equal measure, and yet indispensable. Calcutta is not a city of eras layered politely one atop the other, but a collision site where centuries coexist in a jumbled simultaneity.

To stand in the midst of it all, to breathe this chaos, is to grasp that the city is not simply alive—it is a system, a kind of chaos engine that generates its own improbable order. Its contradictions hold, not because they make sense, but because they refuse to do otherwise. The morning’s cacophony—horns, vendors’ cries, crows, arguments, tea cups breaking—is not just sound. It is Calcutta speaking itself into being once more, reasserting, with unrelenting vigor, its identity as a place both unbearable and irresistible, disheveled and brilliant, doomed and eternal.