Babumoshai

A satirical deep dive into the daily life of a modern Bengali lower middle-class family. This essay explores the unique blend of frustration, disembodied nostalgia, and philosophical constipation that defines the 'Babumoshai' experience in Calcutta.

7/20/2025

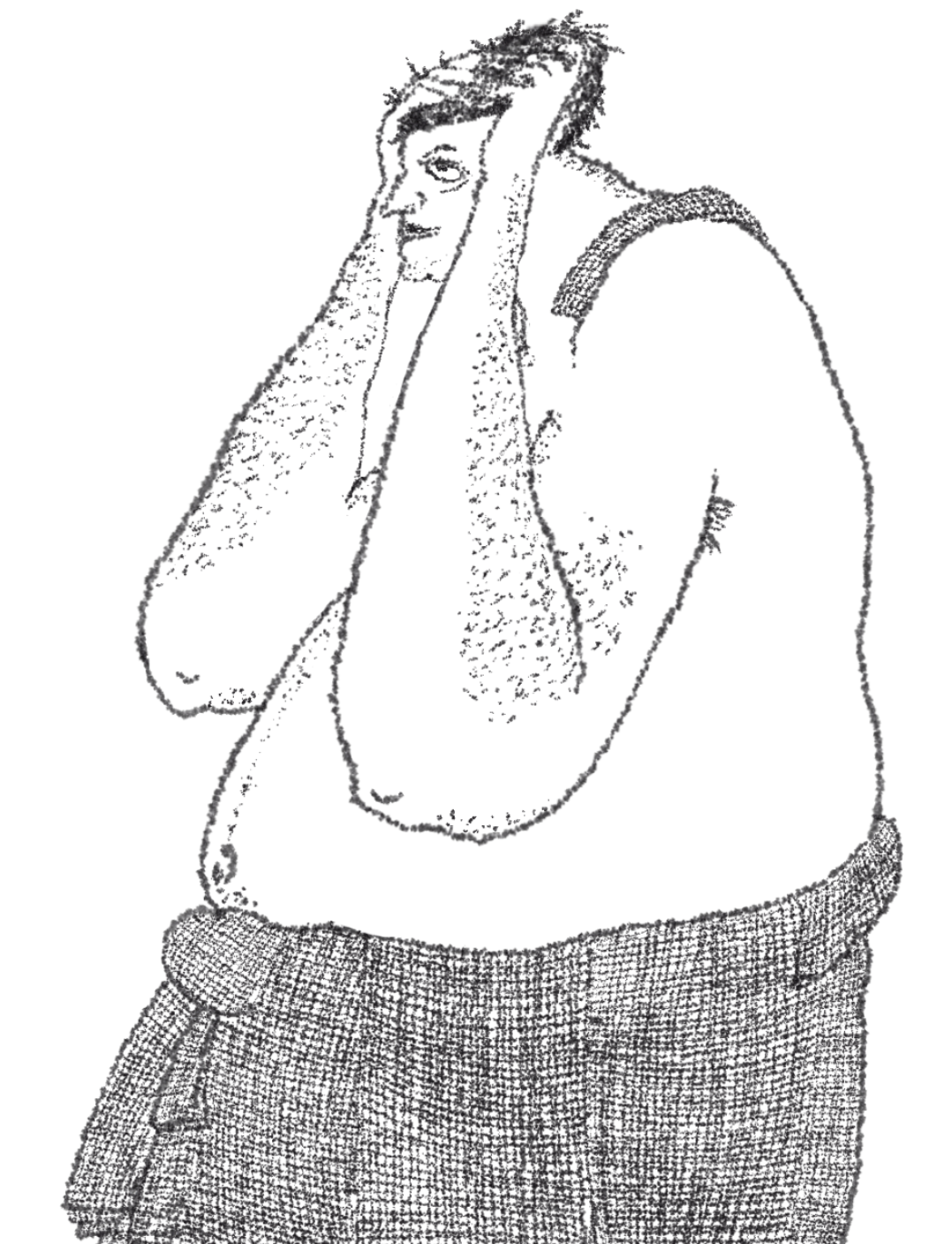

Calcutta, the bustling urban carcass pretending to breathe, thrives on a diet of philosophical constipation, disembodied nostalgia and chronic dissatisfaction. The Bengali lower middle-class family—this ambitious little social experiment, caught permanently between intellectual diarrhoea and economic constipation—is forever trapped in a Kafkaesque limbo of EMI hell and LIC policy redemption fantasies stymied by reluctance to frivolous chores like, for example, the urgency to lookup a word in the dictionary, or hold off passing matter at bowel distensions at life detriment. Each morning, a Bengali middle-class dad, wakes up, acting or actually frail, already disappointed by his undersized existence, grouching about humidity (like he just now discovered it’s moist out there), muttering plaintively unprintable things to the malfunctioning and diminutive objects around, especially his eternal nemesis. The fan creaks and shudders, spinning less out of mechanical duty than stubborn vengeance against Newton’s laws of motion. The lethargy of the fan blades and the sounds it makes are however matching its owner.

Calcutta, the bustling urban carcass pretending to breathe, thrives on a diet of philosophical constipation, disembodied nostalgia and chronic dissatisfaction. The Bengali lower middle-class family—this ambitious little social experiment, caught permanently between intellectual diarrhoea and economic constipation—is forever trapped in a Kafkaesque limbo of EMI hell and LIC policy redemption fantasies stymied by reluctance to frivolous chores like, for example, the urgency to lookup a word in the dictionary, or hold off passing matter at bowel distensions at life detriment. Each morning, a Bengali middle-class dad, wakes up, acting or actually frail, already disappointed by his undersized existence, grouching about humidity (like he just now discovered it’s moist out there), muttering plaintively unprintable things to the malfunctioning and diminutive objects around, especially his eternal nemesis. The fan creaks and shudders, spinning less out of mechanical duty than stubborn vengeance against Newton’s laws of motion. The lethargy of the fan blades and the sounds it makes are however matching its owner.

This unnuanced man, our typical Babumoshai, armed with a torn newspaper folded precisely to the job section he’ll never read, launches himself heroically into the gory arena called public transportation. Battling with elbows sharper than tamahagane Japanese samurai steel, he wields Newton’s third law of motion—every shove has an equal and opposite shove back—only to arrive late at a job where promotion is as mythical as spontaneous orgasm. Here, he pretends to work—fudgel, the boss pretends to pay, and everybody pretends to believe in karma, destiny, and provident fund withdrawals.

At home, his teenage child, that damned revolutionary-in-pyjamas who goes to the Jadavpur University, oscillates between communism and TikTok trends faster than the electron jumping orbitals in Bohr’s atomic circus. He protests capitalism by demanding an iPhone, denounces tradition by loudly reading Tagore in English (pronounced with an accent of no particular Occidental leaning and suspiciously close to diarrheal urgency), and mistakes his hormonal indignation for social activism. The TV drones in the background—bald cuckold male politicians or their belligerent queens spewing economic theories that could only have emerged from sustained cerebral hypoxia, while Bengali soap operas portray women weeping rivers of glycerin tears because they mistakenly added one extra grain of salt to the in-laws’ fish curry.

Meanwhile, the profusely sweating post-menopausal Bengali mom juggles pots, pans, and generational guilt eternally in an air-deprived kitchen. She’s constantly advising her son to study science (pronounced “shaainshh”) and her daughter to be feminist (within marriageable limits, of course). She faithfully worships Lakshmi for prosperity, Saraswati for wisdom, and the Samsung fridge for not going kaput, yet again. “Everything is infuriatingly inflation, I tell you!” she shrieks liltingly—implying that the mustard oil that the fish is swimming around frying itself is worth more than her paltry wedding jewelry. Her bitterness, outrage, profound and seasonal, emerges rhythmically like the monsoon, predictably soaked in nostalgic tears and abject hopelessness.

This lower middle-class North Calcutta angst itself is an ironic inheritance, passed down like arthritis and acidity tablets. This generation, raised on fixed syllabus-constipated cathartic revolutionary verses of Nazrul Islam and Tagore, drowns in romantic frustration and economic rectum retention, while wishing desperately to escape—perhaps to America, or at least Bangalore—grass being not Bengali apparently and therefore greener. But no sooner do they leave Calcutta, than nostalgia sets in, a long segmented parasitic emotional tapeworm that sheds sentimental nostalgia in the environment like excreta, compelling the Bengali to start Durga Puja clubs in American suburbs, where confused Caucasian Jesus or Jehovah jamboree watch in mild horror at the idol immersion in chlorinated community pools.

Why does the culture and its critters endure though? This is genetic masochism, karmic constipation, and the stubborn Bengali ego that thrives on intellectual vanity and cultural elitism while struggling to pay EMI on a one-bedroom apartment in South Calcutta—now a proud euphemism for the other bank of the toilet drain than any direction or place! Today’s Bengali angst thrives precisely because it cannot be solved: each complaint generating another, each dissatisfaction spawning offspring of absurd yet poetic proportions, each paradox becoming the very essence of their existence, without ever knowing the root cause, trying to understand the premise or really ever attempting to solve the problem—symptomatic of not just Bengal but India as a country unfortunately, a funny pathology that needs more people to notice it.

To be Bengali, lower-middle class, and living in Calcutta is to master the art of living just adequately enough to complain beautifully, bitterly, and endlessly—right until death, the ultimate relief, becomes itself yet another inconvenience because it interrupts their schedule of complaining.