Anaximander's Revolution

Explore the groundbreaking idea of Anaximander of Miletus, the ancient Greek philosopher who first imagined the Earth as a body floating in space. This post delves into the philosophical revolution that solved the mystery of the sun's nightly journey and gave birth to cosmology.

7/28/2025

There’s a particular quality to the sky over the plains of Bengal, especially as the sun begins its languid descent. The horizon feels impossibly wide, a vast, flat line separating the solid earth from the ethereal dome above. It’s a view that feels primordial, fundamental. You’re here, on the ground. The sky is up there. What could be more obvious?

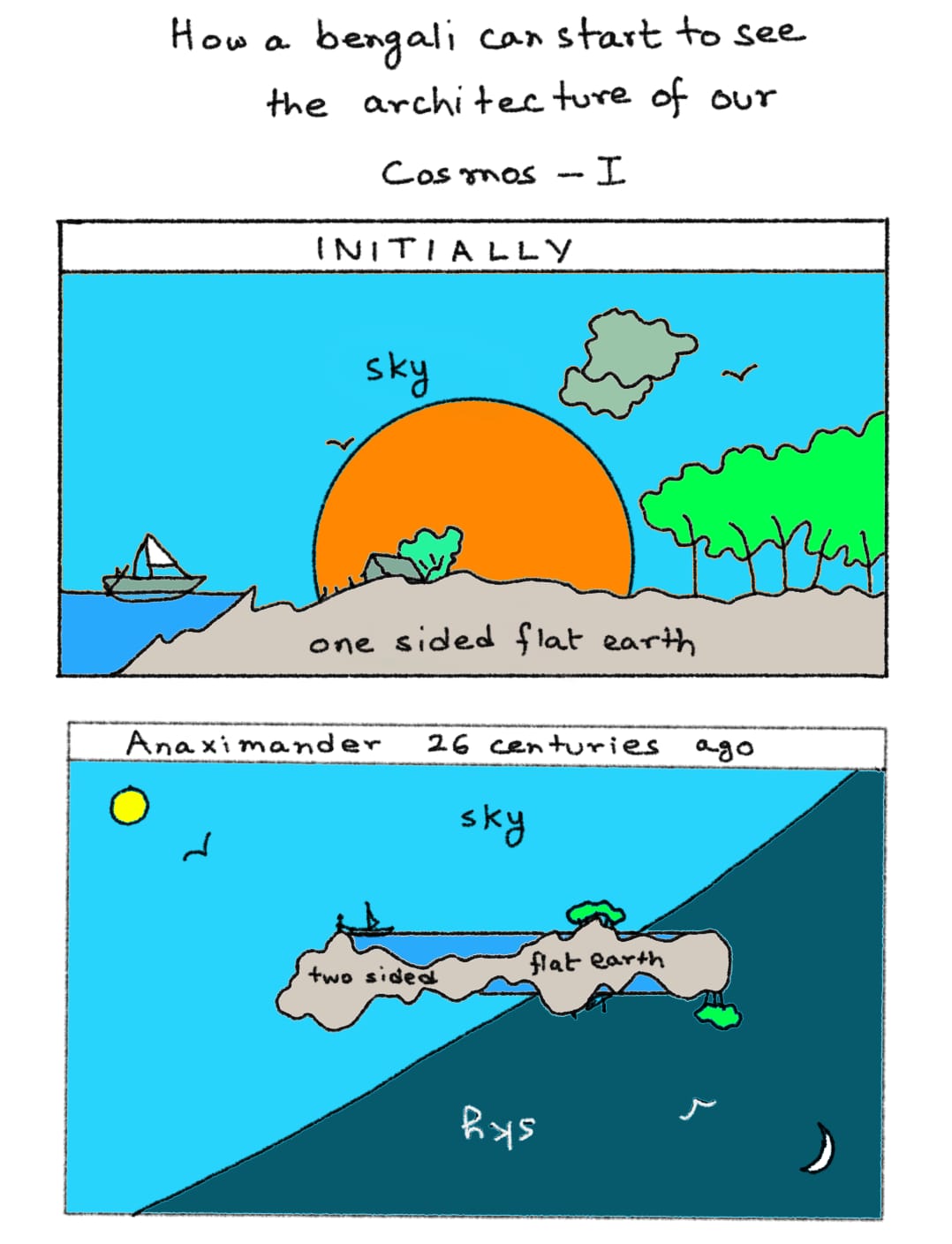

This is the cosmos of our intuition, the one we are all born into. It’s a world built on a simple, reassuring duality: a floor beneath our feet and a ceiling over our heads. My little sketch accompanying this post captures this sentiment perfectly. In the “INITIAL” panel, we see it all: the ground, the sea, the trees, and the sky. A one-sided, self-contained world. The sun travels across the top and, well, it goes away somewhere. We don’t worry too much about the particulars.

For millennia, this was humanity’s universe. It was the universe of the Babylonians, the Egyptians, and the early Hebrews. It worked, for the most part. It explained why things fall down and smoke rises up. But it harboured a profound, nagging conundrum. A cosmic loose thread.

What happens to the sun?

And for that matter, the moon, and all those wandering stars? They dutifully sink below the western horizon, only to reappear, fresh as a daisy, in the east the next morning. How? Do they perform some frantic, clandestine dash around the northern edge of the world while we sleep? Is there a new sun every day, forged in some celestial furnace? Or do they sail upon a “night sea” under the world? The explanations were often beautifully poetic, but they felt… ad-hoc. They were patches on a model that was fundamentally broken.

Enter Anaximander of Miletus, a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived a staggering twenty-six centuries ago. Miletus, on the coast of modern-day Turkey, was a bustling hub of trade and, more importantly, of intellectual ferment. And Anaximander, a student of the first-ever philosopher Thales, was contemplating this very problem of the disappearing sun.

His solution was not a patch. It was a complete and utter demolition of the old architecture. It was an idea so audacious, so contrary to every scrap of human intuition, that it rightfully stands as perhaps the first true scientific revolution.

He proposed that the Earth is not a floor. It is an object.

Let that sink in.

Anaximander suggested that the Earth is a body—he pictured it as a flat-topped cylinder, like a drum—hanging unsupported, floating in the centre of an infinite space. It stays in place, he reasoned, because it is equidistant from all other things and has no reason to move in one direction over any other.

The genius of this is not that he got the shape right (he didn’t). The genius is that he conceived of space underneath us. Suddenly, the world wasn’t a single-sided stage; it was two-sided, as my second panel of the comic illustrates.

With this single, magnificent leap of imagination, the nightly journey of the sun was no longer a mystery. It didn’t have to sneak around the edges. It simply continued its circular path, passing cleanly under the floating Earth, to rise again in the east. The sky was not a dome; it was a sphere. There was an “up” and a “down” relative to where you stood on Earth, but in the grander cosmos, there was no absolute up or down. There was only “towards the centre” and “away from the centre.”

This was more than an astronomical insight; it was a philosophical cataclysm. Before Anaximander, the Earth rested on something—water, a giant turtle, the shoulders of Atlas. It needed a foundation. Anaximander freed our world from its moorings. He placed it in the void, subject not to the whims of gods or the support of mythic beasts, but to a principle of equilibrium. It was a naturalistic explanation. This was the birth of cosmology.

Every subsequent cosmic revelation stands on the shoulders of this one. The spherical Earth of Pythagoras and Aristotle, the heliocentric system of Copernicus and Galileo, Einstein’s curved spacetime—they are all descendants of Anaximander’s brave declaration that the Earth is just a thing in a place, not the place itself.

So the next time you watch a sunset, perhaps from a rooftop in Kolkata or a boat on the Padma, take a moment. As the sun vanishes, don’t just see it as the end of the day. Picture its journey continuing, unseen, beneath your very feet. You are standing on a colossal object suspended in the middle of everything, held in place by nothing at all. It’s a terrifying, exhilarating, and profoundly beautiful thought—a gift to us from a mind that, twenty-six centuries ago, dared to turn the whole world upside down.